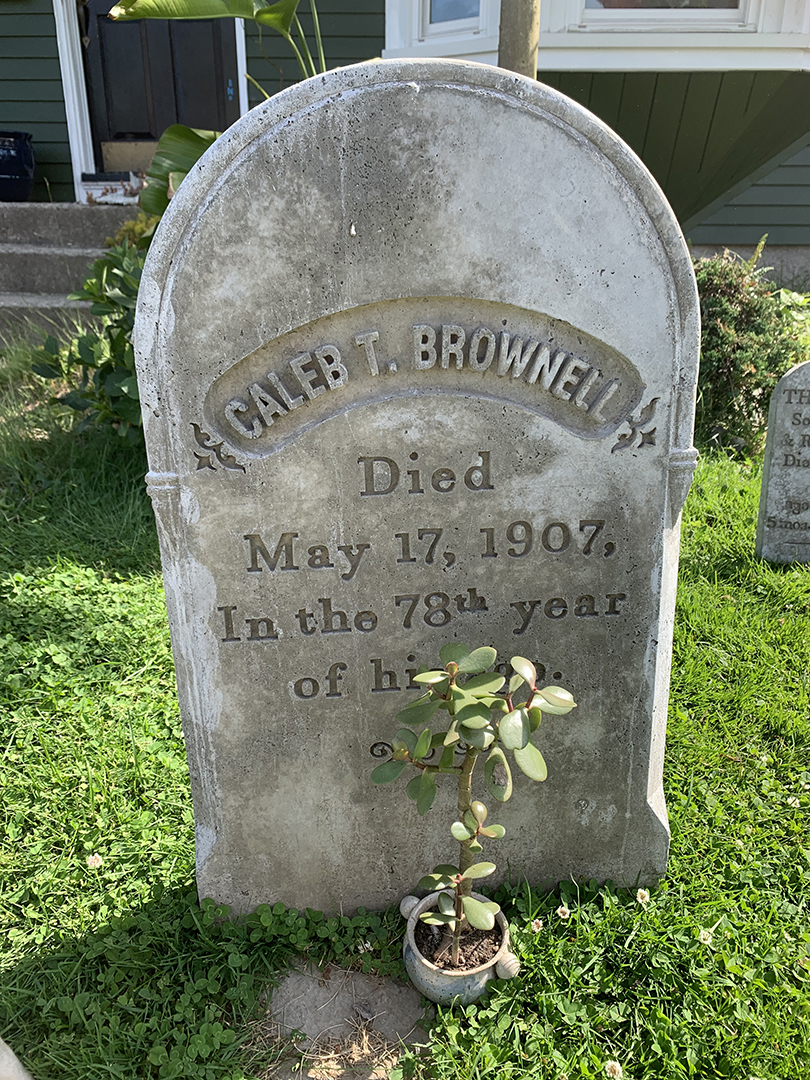

Caleb T. Brownell

This rounded-top marble tombstone for Caleb T. Brownell, who died in 1907 at age 78, reflects the modest, enduring style common in rural New England at the turn of the century.

The carved name banner and subtle flourishes suggest late Victorian influence, while the weathered surface hints at its original white marble—popular in the 1800s but prone to staining over time.

Likely a farmer or tradesman from Little Compton, Caleb would have lived a working-class life rooted in land and community. The arched design symbolizes a gateway to the afterlife, marking his passage with quiet dignity.

The carved name banner and subtle flourishes suggest late Victorian influence, while the weathered surface hints at its original white marble—popular in the 1800s but prone to staining over time.

Likely a farmer or tradesman from Little Compton, Caleb would have lived a working-class life rooted in land and community. The arched design symbolizes a gateway to the afterlife, marking his passage with quiet dignity.

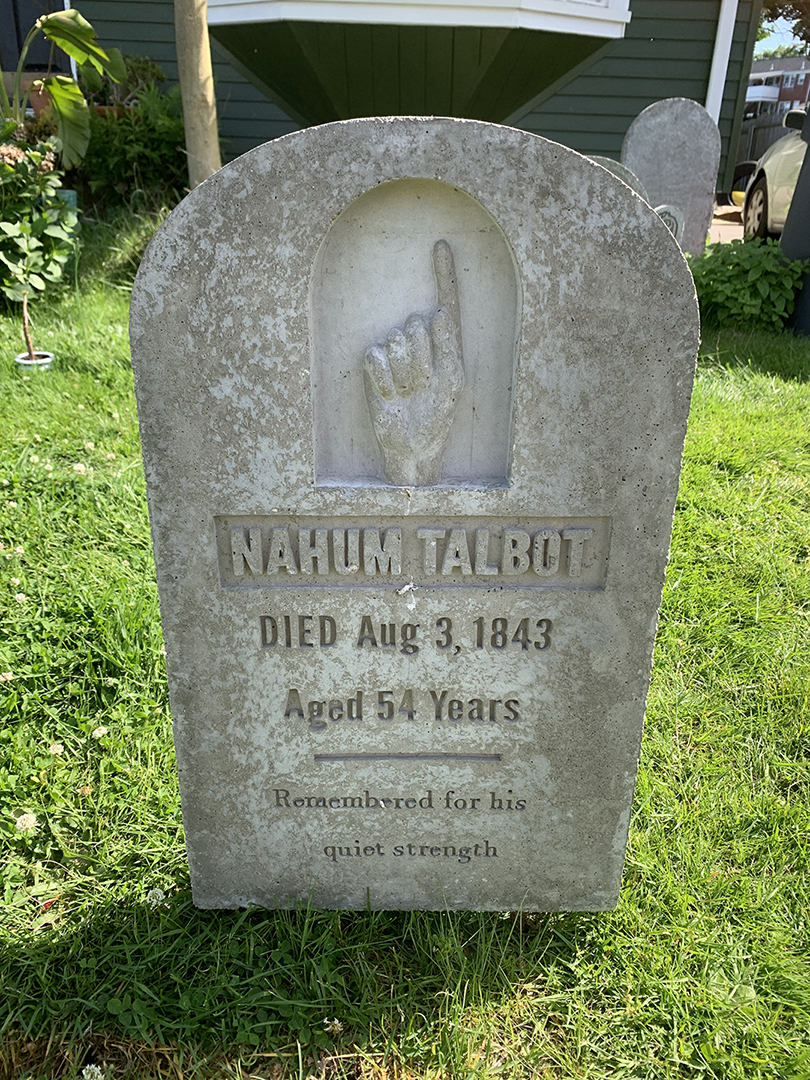

Nahum Talbot

This mid-19th century tombstone for Nahum Talbot, who died in 1843 at age 54, would most likely have been carved from brownstone or marble. It features a raised carving of a hand pointing upward—an enduring symbol of the soul’s ascent to heaven, common in Protestant iconography of the time.

Its rounded top and recessed panel reflect early Victorian gravestone design, often reserved for individuals of modest means but meaningful community presence. The epitaph,

“Remembered for his quiet strength,”

paired with the spiritual imagery, suggests Nahum was a steady, respected figure—likely a laborer, craftsman, or small landowner in a rural New England town.

Its rounded top and recessed panel reflect early Victorian gravestone design, often reserved for individuals of modest means but meaningful community presence. The epitaph,

“Remembered for his quiet strength,”

paired with the spiritual imagery, suggests Nahum was a steady, respected figure—likely a laborer, craftsman, or small landowner in a rural New England town.

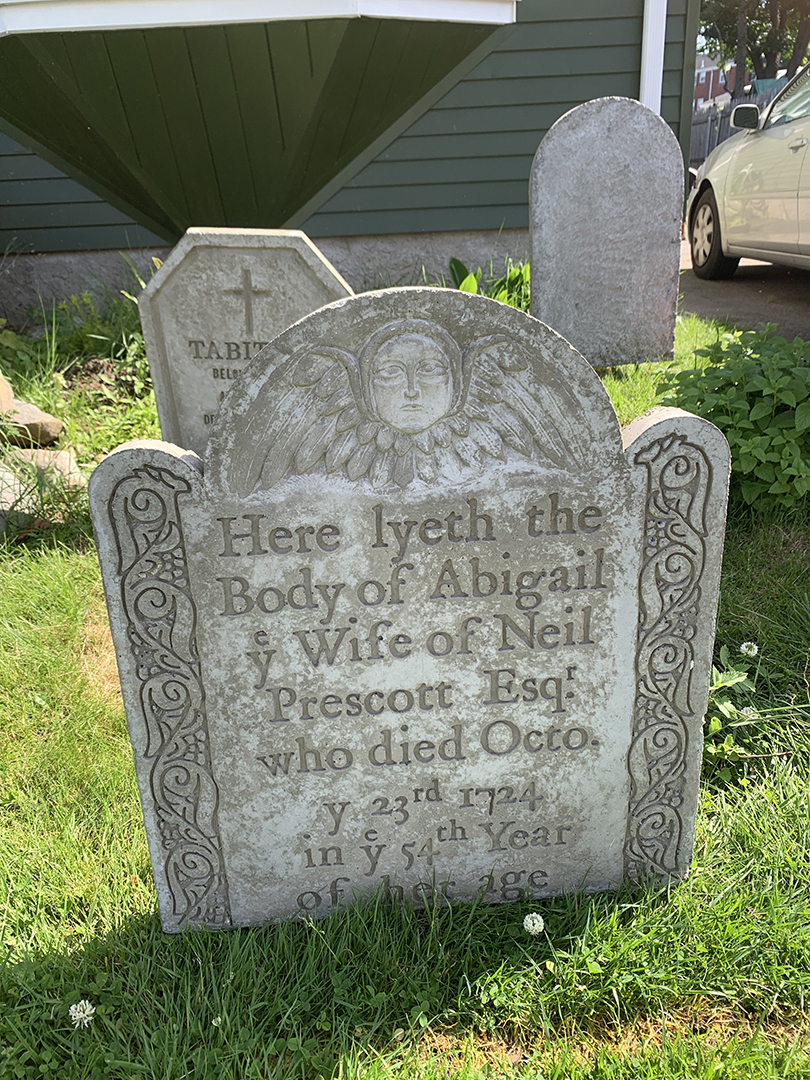

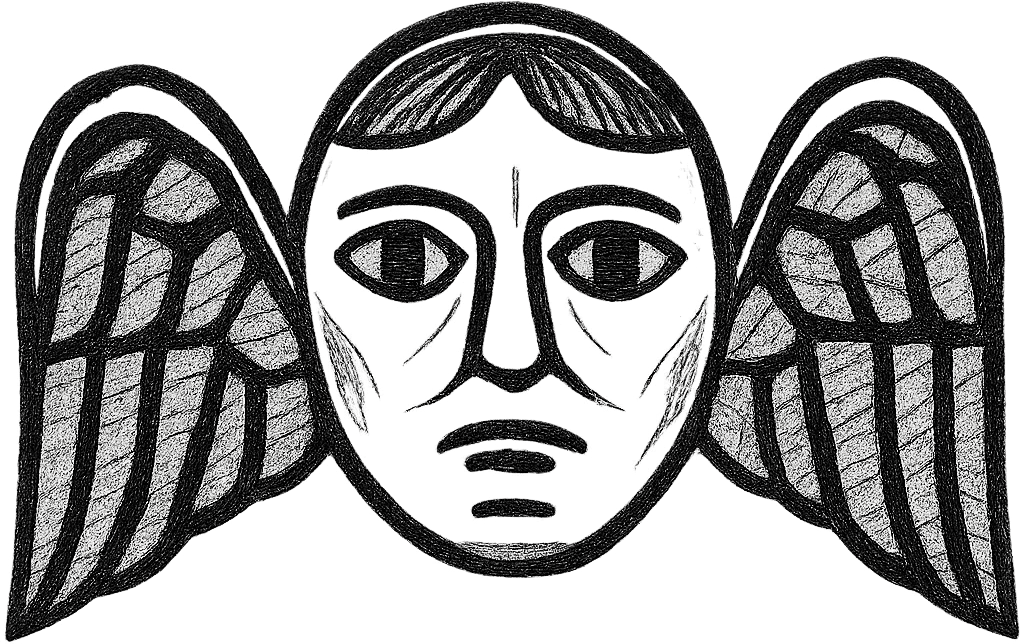

Abigail Prescott

This 1724 marker for Abigail Prescott is styled after early colonial New England slate gravestones, known for their arched tops, hand-carved borders, and striking soul effigies like the winged face seen here—meant to symbolize the ascension of the soul.

Originally, a stone like this would almost certainly have been carved from local slate, prized for its durability and fine carving surface.

As the wife of “Neil Prescott, Esq.,” Abigail likely belonged to the upper tier of colonial society, possibly married to a magistrate, merchant, or landholder in early Rhode Island.

Her stone evokes a time when death was ever-present, yet deeply spiritual, and memorials served both as tribute and theological reminder.

Originally, a stone like this would almost certainly have been carved from local slate, prized for its durability and fine carving surface.

As the wife of “Neil Prescott, Esq.,” Abigail likely belonged to the upper tier of colonial society, possibly married to a magistrate, merchant, or landholder in early Rhode Island.

Her stone evokes a time when death was ever-present, yet deeply spiritual, and memorials served both as tribute and theological reminder.

Abel

This simple cross-shaped headstone reflects a shift toward more minimalist Christian memorials common at the turn of the 20th century. Unlike the ornate carvings of earlier eras, this form emphasizes quiet devotion and resurrection symbolism. It would likely have been made of granite, which by 1900 had become the preferred material for its durability and clean lines.

The plain block lettering and unadorned form suggest Abel may have lived a modest life—perhaps a farmer, laborer, or churchgoer in a small New England town—remembered with dignity and faith, not flourish.

The plain block lettering and unadorned form suggest Abel may have lived a modest life—perhaps a farmer, laborer, or churchgoer in a small New England town—remembered with dignity and faith, not flourish.

Tabitha

Tabitha’s octagonal-topped headstone reflects a transitional period in funerary design—moving away from ornate Victorian styles toward simpler, more geometric forms. The cross at the top and straightforward inscription suggest quiet religious devotion and a focus on family legacy.

A woman born in the early 1820s and living into her 80s would have witnessed enormous change in New England, likely spending most of her life as a homemaker, farm wife, or matriarch of a rural household.

A marker from her time would most likely have been carved from white marble, still common in 1901 despite its tendency to weather and fade.

A woman born in the early 1820s and living into her 80s would have witnessed enormous change in New England, likely spending most of her life as a homemaker, farm wife, or matriarch of a rural household.

A marker from her time would most likely have been carved from white marble, still common in 1901 despite its tendency to weather and fade.

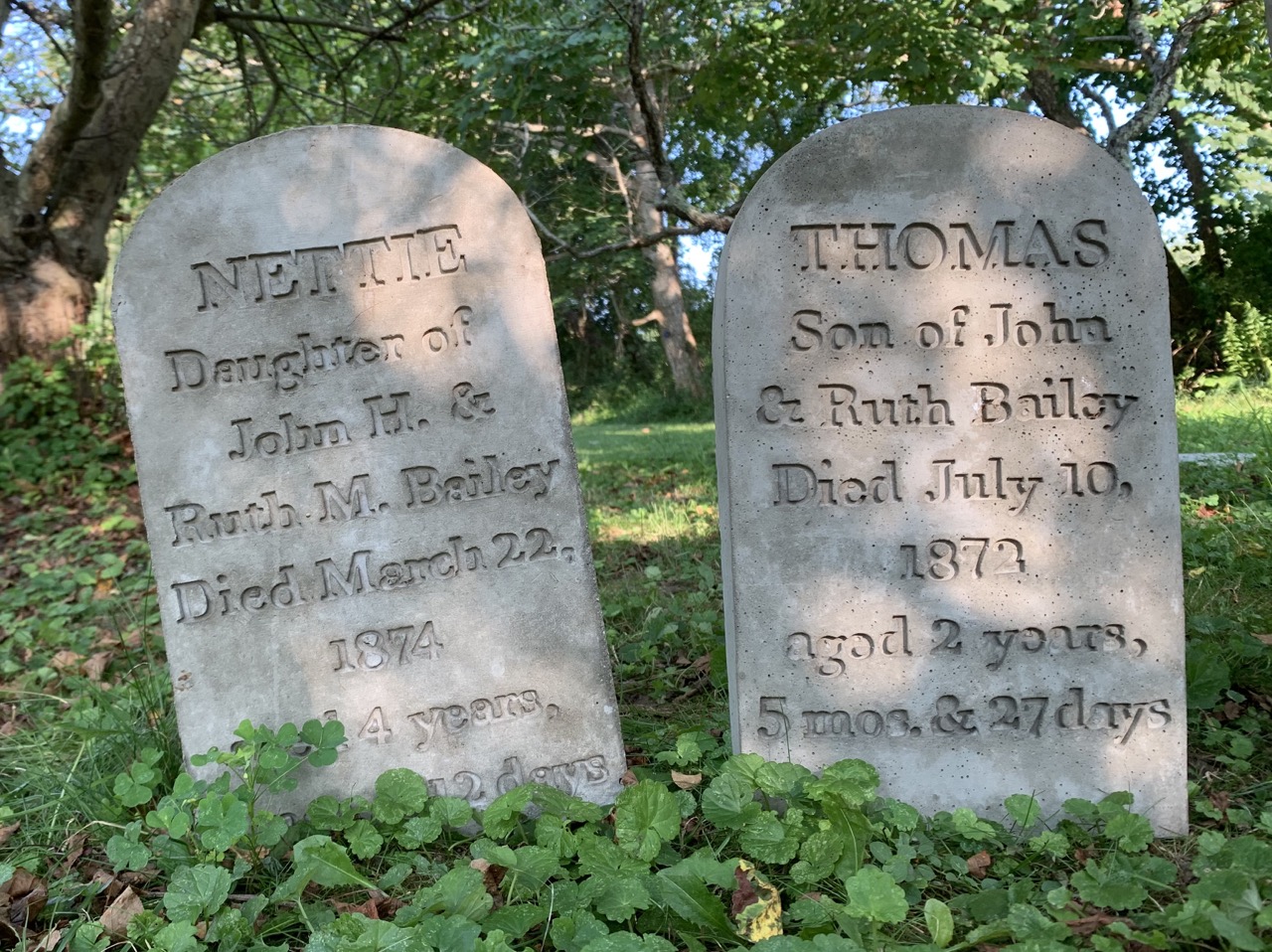

Nettie & Thomas Bailey

These small, arched headstones for Nettie and Thomas Bailey—siblings who died just two years apart in the 1870s—are modeled after traditional Victorian-era children’s markers, simple in shape but heartbreakingly precise in detail. The exact ages down to the day reflect the period’s deep reverence for young lives lost, and the grief-stricken practice of recording every moment they were alive.

While these examples are cast in concrete, originals from this era were typically carved from white marble, which was affordable, easy to shape, and commonly used for children’s graves. The uniform lettering and modest size suggest a working-class family, likely rural, doing what they could to remember their children with dignity and care

While these examples are cast in concrete, originals from this era were typically carved from white marble, which was affordable, easy to shape, and commonly used for children’s graves. The uniform lettering and modest size suggest a working-class family, likely rural, doing what they could to remember their children with dignity and care

Hale Family

The Hale family stones reflect the styles of their time. Elias Hale and Martha Hale would likely have been commemorated in brownstone, common in colonial New England for its availability and workability. Their son Ebenezer Hale may have had a slate or marble marker, as marble began gaining popularity in the early 1800s for its smooth surface and refined look.

These markers, simply shaped and modestly inscribed, reflect the reserved dignity typical of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

These markers, simply shaped and modestly inscribed, reflect the reserved dignity typical of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.